Each provincial Easter Seals organization offers a variety of support and recreational programs tailored to the needs of its demographic. For example, one of the program Easter Seals offers across Canada is camps for families, children, youth, and adults.

As a kid, camp was the event of the summer, maybe even the year for me. I lived for it. I counted the days until I could be back on the magical peninsula of Easter Seals’ Merrywood Camp in Perth, Ontario.

Camp Merrywood was the one place where everything was accessible. Where I could be myself, and it was pretty much the only place where my Cerebral Palsy wasn’t an issue, problem, or barrier. In fact, having a physical disability, such as CP, was a requirement to attend. We were the majority; thus, the environment was built with us in mind.

Everything at camp is accessible, including automatic doors, ramps, and paved paths everywhere. And when they couldn’t make an area or activity 100% physically accessible, such as getting in and out of a canoe or sailboat, they had young, strong counsellors trained and available to help as needed.

I grew up going to physical therapy and social programs at Grandview Children’s Centre, so I had a group of peers and friends with disabilities. However, this is not everyone’s experience. For many, camp is the only opportunity to spend time with peers with similar experiences in an environment that was made for them. It can be very isolating and tiring to be the only one with a disability in most of your environments.

Whether it be at camp or other recreation programs, time with disabled peers is an invaluable experience for kids and youth living with disabilities.

But beyond camps, what other recreational programs are available for adults with disabilities – particularly when they age out of recreation programs designed for youth?

No matter how old we get, we should always be open to and looking for new accessible experiences that provide life-long opportunities to be active, learn, explore, and socialize. Trying something new might be scary, but it’ll also be fun and rewarding.

Here are just a handful of accessible recreation options to get you started.

Skiing

By the fall of 2016, I had been out of university and working from home for a year. I was beginning to think about the impending winter. I dreaded how the cold and snow would keep me stuck inside even more than my work already did.

That summer, I was hired by Easter Seals to work as a counsellor at Camp Merrywood., Some of the older campers told me about how much they loved to sit ski. While I’d known about adaptive skiing and had a friend who was also a sit-skier, it had never really occurred to me to try it. No one in my family skied. I wasn’t athletic. And I hated winter.

But I needed an activity to help get me out of my apartment and socialize. Downhill skiing sounded thrilling, like my beloved sailing on snow rather than water. Research led me to the CADS website (https://cads.ski/en/divisions), where I found ADDS (Adult Disabled Downhill Skiers), a local club that charted a bus (perfect for me as a non-driver) from Toronto each weekend from January to March. While the $300 I would need for both CADS and ADDS fees were reasonable for lift tickets, bus, lessons, and equipment rental, it was more than I could afford at the time. I discovered through a bit more research that the Ontario Federation for CP offers financial assistance for such activities. I applied and was ready to hit the ski slopes within a few weeks.

Fast-forward five years, I love speeding down the hill in a sit-ski. I’m still learning but improving with each season. And I met people who are now some of my best friends, both on and off the ski hill.

Sailing

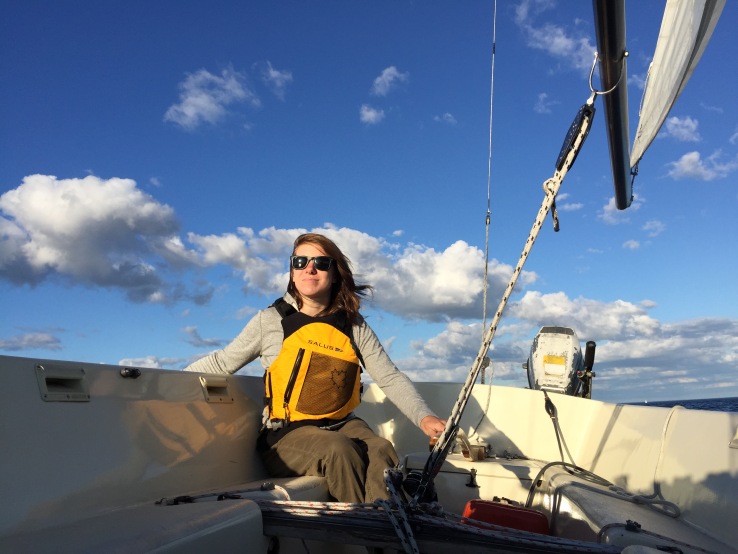

Sailing has been one of my favourite activities since my early days at Easter Seals Camp, and I was often curious if it was possible to find accessible sailing closer to home. So when I moved to Toronto for university in 2011, I was introduced to AbleSail, a network of non-profit organizations in cities across Canada offering accessible sailing programs and opportunities to youth and adults living with disabilities. Thus far, I’ve sailed with friends and volunteers in Toronto and St. John’s, Newfoundland. I love the feeling of the wind catching the sail and propelling the boat forward. Like skiing down a hill, speeding along on the water is thrilling.

Rock Climbing

While I haven’t tried adaptive rock climbing yet, I recently heard about it from a friend, and now it’s on my list of things to try next. I loved bungy jumping, sky diving, and Easter Seals’ Drop Zone fundraiser, so I think rock climbing could be right up my alley. It seems like another great way to stay active and get a bit of exercise. The Canadian Adaptive Climbing Society offers programs in Ontario and British Columbia.

Wheelchair Basketball, Sledge Hockey, and Para-swimming

These might be three of the most well-known adaptive sports for people living with disabilities. I initially assumed they were so common that I almost didn’t include them in this article. While I’m not skilled in these sports, I know many enjoy wheelchair basketball, sledge hockey, and para-swimming. I’ve heard many stories from friends about how these sports have provided Canadian athletes with disabilities opportunities to learn new skills, stay active, make friends, and even travel.

Travelling

This last one might seem crazy to some but hear me out.

Travelling can be challenging for people living with disabilities, often requiring courage and planning. But it’s possible! There are so many exciting places to see and people to meet. There are so many adventures to be had. You could start small. Take a day or weekend trip to explore a local city. Visit a friend who lives out of town but is maybe only a train ride away.

t would be easy to say that my love of travel started in 2014 when I spent a semester studying and exploring New Zealand. This was when I realized I could travel independently, find or create accessibility, and, along the way, make friends from around the world.

Since then, I’ve toured much of the UK and Ireland; spent a long weekend in Italy; vacationed in Mexico; followed my favourite band to San Diego; roundtripped from Houston to New Orleans and Austin; and saw my first real-life iceberg in St. John’s, Newfoundland. Just to name a few adventures.

But my interest in travel started with my family and friends when I was much younger. At least a couple of times a year, my parents would pack my two younger siblings and me in the car for cottage and camping weekends, often exploring the local town, food, and attractions. We also loved weekend trips to Niagara Falls, where we could explore Clifton Hill, swim in the hotel pool and order room service. Then, when I was a teenager, we started flying to Alberta and California to visit family and then taking roundtrips in and around those places. These family adventures showed me there was more out there to see.

Now that I’m an adult, I always look for accessible travel opportunities. Thus far, organized and hop-on-hop-off of bus tours have been the biggest key to my success. Most cities have a hop-on-hop-off tour bus that hits all the must-see spots. I usually ride the route twice–once to see the city and hear the history, then again to get to where I want to go.

Organized bus tours are also a great way to cover a lot of ground, stopping along the way to see the sights and make friends with like-minded travellers who are happy to lend a hand when needed. Bus drivers are well informed and usually glad to help me make my experience as accessible as possible, whether by turning a walking tour into a driving tour or calling ahead to the hostel to ensure I have a room on the ground floor with an ensuite washroom.

When planning a trip, I do a lot of research to familiarize myself with the area. For example, is there public transit––is it accessible, and how much does it cost? What do I want to see and do? Where can I stay? What are the food options? Are there options and discounts for people with disabilities? While many like to stay outside the touristy areas to save money and avoid crowds, I find that it is often most accessible to stay where the action is because everything I need is nearby––including transit to other areas I may want to visit.

Several blogs, websites and companies also specialize in accessible travel. It is always helpful to learn from those who have come before. Access Now is a tool that puts this idea into practice by crowd-sourcing accessibility information of public places from the people with disabilities who have been there. Not sure if a specific restaurant is accessible? Look it up on Access Now. I recently discovered Accessible GO, which is excellent for finding accessible hotel rooms. And March of Dimes Travel offers everything from organized day trips to cruises for travellers living with disabilities. And last but certainly not least, Easter Seals’ Access 2 Card Program is a great way to explore Canadian attractions more affordably with a friend/support person in tow. Research is key and can be a lot of fun!

Trying new things can be nerve-racking. However, we must not let fear hold us back from opportunities to learn, grow and make new friends, partially into adulthood. We never know where it could lead; maybe we’ll find a new passion.

Originally published by Easter Seals Canada.

I helped to design, build and write content for CP-NETs Five-Year report. It was an excellent opportunity to practise and further develop my writing, editing and web-design skills. Check it out

I helped to design, build and write content for CP-NETs Five-Year report. It was an excellent opportunity to practise and further develop my writing, editing and web-design skills. Check it out